A GUTTED PURSE

on the sentiment of material belongings

& the lore of what’s in my bag

words by Lily Moskowitz

Image Courtesy of the MET Museum.

Theatre Accident, New York. Irving Penn, 1947.

Dye transfer print.

One pearl earring, a timepiece, some metal receptacle, and a single

splintered cigarette, its tobacco confettied out.

In 1947, American photographer Irving Penn shot an image of a golden satchel slumped upon the carpet, its innards unceremoniously dumped on the ground. Entitled “Theatre Accident, New York,” the picture spins off of the classically arranged still life in favor of a more involuntary composition, in which objects do not appear intentionally fixed but are instead haphazardly splayed against a linoleum background. Keys, binoculars, pills, one lonesome hair pin.

Though the historical context of this image is unknown, the objects depicted in this photograph gesture at a lighthearted crime scene; through some small deductive maneuvers, the viewer may string together a cohesive narrative of the bag’s owner, whose foot is pictured alongside the material disarray. Where this person was, of course, is given to us – the theatre – yet who they were must be inferred. Why they might have dropped their bag, what play they were seeing, whether they were coming or going, all left up to the viewer to conjecture.

Subtle and suggestive, “Theatre Accident, New York” proposes that the contents of a bag hold clues to an unsolvable riddle. Irving Penn held a reputation as an “intensely private man” who, despite his critically acclaimed career at Vogue, himself “avoided the limelight” (Penn). In the printing of this photograph, Penn revealed the intimacy not of his own life, but of the life of his photographed subject, whose upended bag has stripped her completely of her privacy. Vulnerability projected onto subject, into object.

We burden ourselves with objects as if we were a mule; they become symbols of our failed destiny, they are charlatans trying to sell us a bled-dry folly of time. Every object is a clock, an hourglass on which time has passed.

From “Objects” Alda Merini

The elusive contents of What’s In Our Bags are no longer a mystery but a mythology dense with narrative. As consumption pervades our personalities, we slowly come to be defined by our ownership and our objects. Identity, then, can be found inside of the purse.

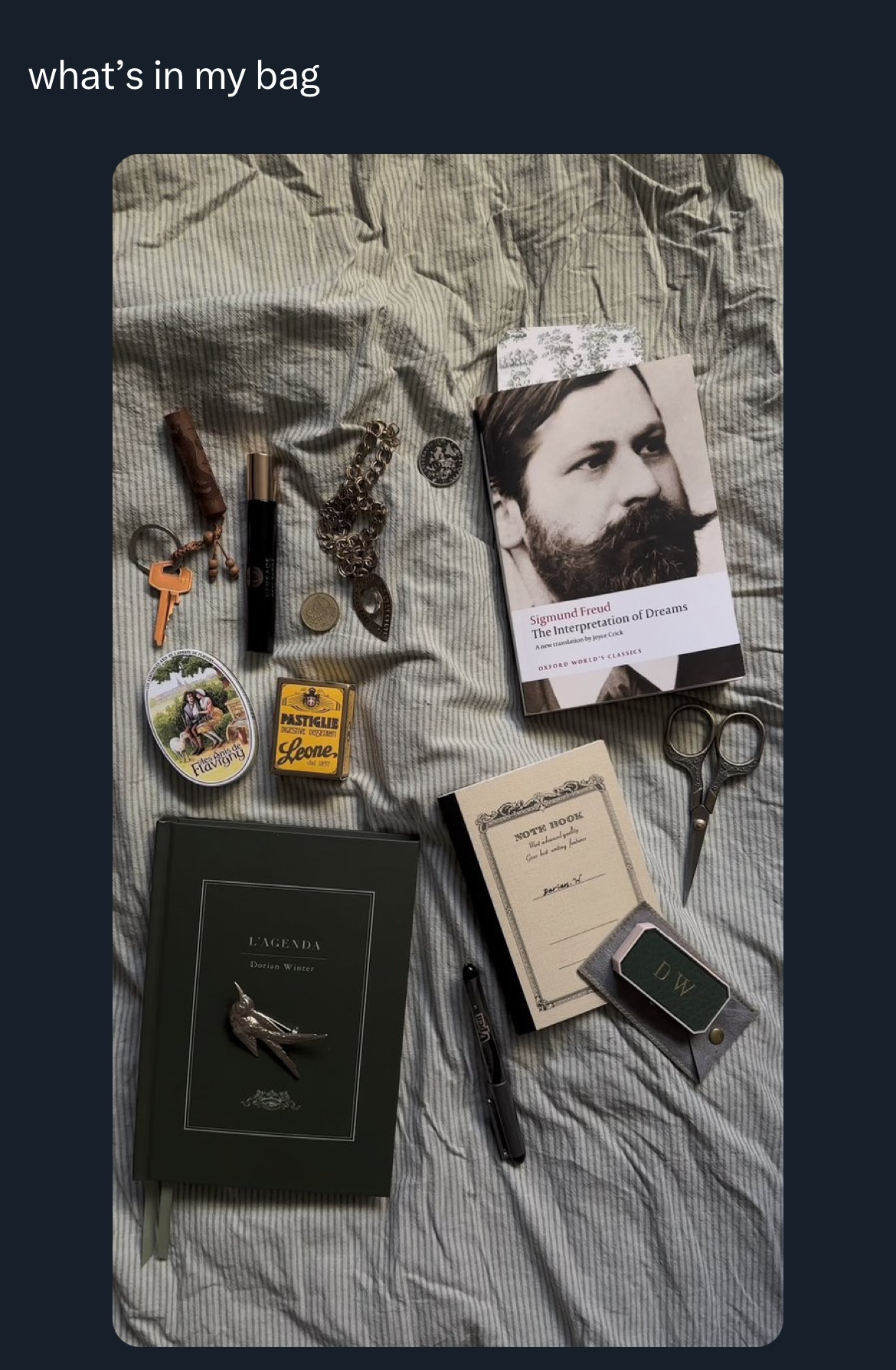

It is perhaps from Penn’s “Theatre Accident, New York” that the “What’s In My Bag” trend originates: the act of turning one’s bag inside out and revealing the debris of one’s day to day, which has cemented into a universal media phenomenon spilling over into both social and editorial spaces. While Twitter aesthetes post photo spreads featuring the contents of their vintage clutches and hand-knitted crossbodies – often carefully sorted into visually pleasing piles — major fashion and culture publications have similarly taken on the concept as an alternative method to interviewing recognizable figures of fame.

And here is the last muscle of our effort falling to the ground: gathering scattered, extinguished objects, objects which tell badly lived poems and which have the sense of endurance.

From “Objects” Alda Merini

On par with the People Magazine phenomenon of “Celebrities: They’re Just Like Us”, in which Jennifer Aniston shops for groceries and Jake Gyllenhal spills his morning coffee, the What’s In My Bag trend attempts a humanization of celebrity. Yet rather than conversing with actors and creators about their production methods, their daily schedules, their beauty routines – essentially digging for secrets on how they manage to be so successful – the What’s In My Bag style interview instead probes the inner life of a public figure through the objects that fuel their day-to-day.

British Vogue’s ‘In The Bag’ Youtube series, for instance, invites celebrities to unearth the contents of their purses and pouches– from Julia Fox's Mowalola handbag to Precious Lee’s Telfar tote. What’s In My Bag is the shuddering fall of the velvet curtain and a peek behind the scenes of the show: Julia Fox totes around a copy of her own memoir, quite literally carrying her life in her purse. Emma Watson carries inside her Prada nylon a freckle pen (for when she is without sun), a handle of gin (for emergencies), Zicam (to prevent her from getting sick), a SleepMaster eye mask (for train naps), and, in true Hermione Granger fashion, both a Kindle and a physical copy of T.S. Eliot’s The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock (gifted to her as a graduation present by Perks of Being a Wallflower director Steven Chboksy, who inscribed it with “These words are forever. So is your passion for learning, for living, for literature”). In these items we see Watson’s hunt for rest and relaxation amidst incessant work, the coping mechanisms and outlets that enable her to function and flourish.

GQ’s channel similarly characterizes celebrity through a survey of their most essential objects. In videos like 10 Things Lil Yachty Can’t Live Without, we feel closer to the rapper upon the discovery that he carries two wallets, his grill and a box of Thin Mints. Other guests on the segment include Sydney Sweeney, Travis Scott, Erykah Badu, Roddy Rich, Olivia Rodrigo, Denzel Curry, Megan Thee Stallion... The list goes on. Through this form of glorified show-and-tell, we learn that Lil Yachty holds deep nostalgia for Girl Scout Cookies because they remind him of his dad. That Jonah Hill is so addicted to Celsius Water that he is often mistaken as a brand ambassador. That Jacob Elordi keeps a cigarette case full of Post-It Notes in his pocket, one of many totems that he has kept on his person in order to embody each character that he plays. Elordi’s technique of grounding his acting performance in a material object particularly suggests personal belongings to be the very souvenirs of our life experience: the talismans of our tastes, our trials, our tribulations.

Everyone asks me of how many objects my house is made up, and of how many hours, of how many silences. Yet no one has ever realized that objects have a precariousness of their own, that they cannot die.

From “Objects” Alda Merini

Clearly we are drawn to these internal glimpses of materiality behind the scenes. Acts of permitted voyeurism – including What’s In My Bag and What’s In My Home – extend to several symptoms of postmodernity, from the attractive transparency of ‘finstas’ on social media to the supersaturation of Day in My Life Tiktoks and Get Ready With Me vlogs.

Architectural Digest has similarly popularized the house and apartment tour, in which the viewer is turned visitor. Taken into the very living space of an idol and welcomed into the corners of their home (staged as they may well be for the means of production), we become familiarized with the famous through their aesthetic affinities.

The artwork, for instance, that decorates Emma Chamberlain’s eclectic Los Angeles abode was painted by her father – reflecting the influence of her upbringing upon her creative impulses. In Alessandro Michele's Roman apartment tour for Vogue, his ornamental cove of antique chandeliers, portraiture, and porcelain contextualizes the love of beauty and finery that has marked the designer's celebrated career at Gucci.

Dakota Johnson’s springy green kitchen allows us to know her as a fan of emerald and sage, as an amateur chef, as a woman who displays a bowl of limes on her countertop despite her lack of tolerance for their taste. Quoted saying “I love limes. I love them so much and I like to present them like this in my house,” and later admitting on Jimmy Fallon that she is allergic to the citrus fruit, Johnson ironically proves that through a survey of one’s kept and stored objects, there is much to be learned about a person’s identity constructions as well as negations.

Objects pure at heart, which light the distances of my day; objects to which I have told about my best troubles and my celebrations. Objects rarefied by the thrill; objects that I barely manage to find again every day on my way, as if they were pointing me towards a path full of words and shadows.

From “Objects” Alda Merini

There is something unsettlingly intimate about rummaging through someone’s belongings. To specifically glimpse inside of their purse (or backpack or tote bag or otherwise categorized carrying container), however, is to expose the archive of their day-to-day. To excavate the artifacts of their ambitions. A lipstick becomes a chase for beauty. A stick of gum or hard candy is the search for sweetness, the hope to be fresh. A book is what one wishes to know. A pair of headphones is what one wishes to hear (or not hear). A ring of keys is their way home. Small symbols of not only who a person is, but how they manage to become. The concrete dissection of one’s being: the unspoken ingredients of a person. Stories stashed in a sack.

A Fendi Baguette sliced open. A Dior saddlebag torn in half. A Jacquemus Micro Le Chiquito daintily disemboweled, unveiling a tumbling sprawl of guts: lip gloss and an empty dimebag and a few stray $1 bills.

The contents of a bag hold precious information to contextualize, to some extent, both the universality and nuance of humanity. Everyone has a wallet, but not everyone’s is splattered in paint from your last day at the studio, or slotted with Polaroids of your best friend, or chock-full with month-old ticket stubs from your local cinema. Exposing the collections of our material pick-me-ups, our comforts and indulgences, thrusts the root of our sensibilities into fluorescent light. Stark and revelatory.

Documenting the substance of a purse is identity data-keeping. Torn movie tickets and crumpled receipts make up the evidence of our existence. Our unintentional paper trail. As if a container of our consciousness, the matter of a bag is not only the items integral enough to keep on one’s person but the scraps too scattered to notice them lining the floor of the backpack and clinging to its pockets.

Our mortal dust.

Of course, there are qualms to the idea that our personhood has been reduced to the material object. Under this perspective we run the risk of defining our lives only by the products of our own consumption. Commodity bodies and commodity identities. Yet if this symptom of postmodern capitalism – the commercialization of the self – is perhaps beyond our control, beyond saving, we might as well take some pleasure in the way that we engage with and stimulate introspection through our belongings.

Consumer theorist Hartley writes on the phenomenon of self-expansion through the acquisition of material objects. Whether we like it or not, “consumerism facilitates the expansion of the self” in which “individuals expand beyond their corporeal limits through the projection of the self onto objects.” Most poignant in Hartley’s consumer narcissism theory is his definition of the Love Object: “objects that are integrated into the self.. implicitly included in the self.. personified and treated as mirror images of the self or ideal self.” If we can re-classify material superficiality into a thoughtful exploration and articulation of self, then maybe we can simultaneously rewrite the narrative of how we purchase. Buying not to appeal to trends but to incorporate an element of your personality into your living space, your studio, your wardrobe. Durable purchases and expressions of your own existence.

Being and Becoming, embodied in the contents of a Bag.

References

American, Irving Penn. “Irving Penn: Theatre Accident, New York.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/714794. Accessed 27 Dec. 2023.

Hartley, Todd Bruce Allen. “Consumer Theory’s Narcissism Epidemic: Towards a Theoretical Framework That Differentiates the Self and Other.” Journal of Consumer Culture, vol. 21, no. 4, 2021, pp. 932–49, https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540519890002.

The Irving Penn Foundation, irvingpenn.org/. Accessed 27 Dec. 2023.