CONSUMERISM AND THE DEATH OF LOVE

Words by Haleigh Branstetter

Why does real love seem to be buried beneath the ashes of postmodern society? If I was part of my parents’ generation, I would be planning to or already be married by now. Obviously, many things have changed since my parents were 23, including life expectancy and societal gender roles, that have led to the steady increase in the median marital age. However, I truly believe that consumerism has played a larger part than any of us realize, not just in median marital age, but in developing truly loving connections at all. Consumer culture and capitalism have permeated our intimate relationships.

In the 2000s and 2010s, society saw a large spike in social media and online dating apps. These applications have always been somewhat of a spectacle to me. I think about how in the middle ages, the average person only ever knew the 200-250 people living in their village. This is a considerably smaller dating pool compared to now, as we can see 200-250 faces just by scrolling on Instagram for a few hours. Obviously human behavior adapts to the surrounding environment, but I have to sit and wonder if our brains were meant to interact with, or even just see, as many people as we do now.

Online media did not change the dating landscape overnight, however. Industrialism, urbanization and globalization have all increased how many people we meet and interact with in our day-to-day lives. The massification of society in general has allowed us to consume everything in excess, including people.

That being said, dating apps have very uniquely changed how our brain formulates our ideas about relationships and love.

You open an app, you scroll through hundreds of pages and pass judgment on whether you like or don’t like something you see. You utilize functions like a like button or adding something to your shopping cart. Seemingly, dating apps are designed very similar to online shopping applications. Everytime you open Tinder or Hinge or Bumble, you are shopping for people. Courtship has been replaced by consumerism. Making the decision to invest the time to talk, flirt, or even go on a date with someone has been made as casual and trivial a task as purchasing a new shirt. People are expendable and replaceable.

Perhaps this doesn’t seem like an issue at first, but people continue to succumb to the pitfalls of overconsumption. We buy things we don’t need and yet we’re never satisfied. There is an impulsive need to keep purchasing things, a lot of which are essentially the same exact product. The illusion of choice is a pretty elementary idea when it comes to breaking down the facets of capitalism, but it seems this concept is bleeding into our personal lives.

Consumer culture has made it that much harder to be happy or satisfied with nurturing and developing only one romantic connection. The illusion of choice leaves people wondering what else is out there, potentially something better than what they have now. It’s not like it’s hard to try out new relationships; dating apps make romantic opportunities easily accessible at our fingertips. Meeting people doesn’t require leaving your house anymore. The lack of effort it takes to explore new options is, for many I would say, more enticing than exerting the proper effort into one relationship. Perhaps it has even become a compulsion for some to incessantly think about what they are losing out on when they commit to one relationship.

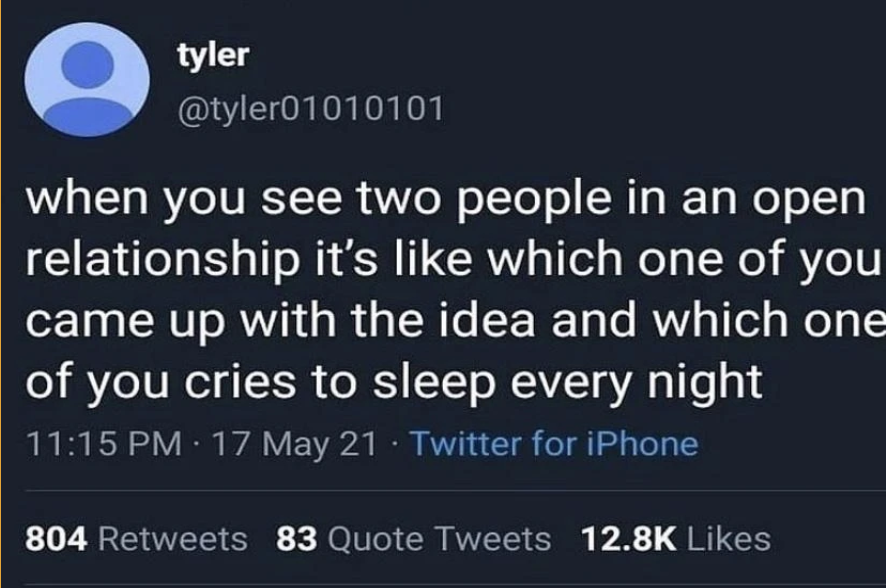

The uptick trend in non-monogamous relationships could also be linked to these sentiments. By settling down with one person, a person forfeits their right to “consume” other people as romantic interests. The same anxieties that a person feels when they are unable to purchase something they want or need now parallels how we conceive of our significant others. Subconsciously, committing to one person breeds a feeling of lack. Non-monogamous and polyamorous relationships allow people to evade the scarcity mindset that may co-occur with a monogamous relationship.

Christopher Lasch actually describes a similar phenomenon in his critique of celebrity culture in The Culture of Narcissism. Lasch points out how people become dissatisfied with the banality of civilian life when they place themselves adjacent to the celebrity culture that had swallowed American society by the late 1970’s:

“The media gives substance to and thus intensify narcissistic dreams of fame and glory, encourage the common man to identify himself with the stars and to hate the ‘herd’, and make it more and more difficult for him to accept the banality of everyday existence.”

The average person is unhappy when they are not accumulating the wealth and fame of Hollywood actors, leading to self-obsession and a focus on climbing the social and capital ladder, which leads to an eventual isolation from the people and community around them. While Lasch is specifically talking about celebrity culture, any facet of capitalism and overconsumption leads people to feel the same sentiments. Capitalism’s promise of eventual grandeur leads to dissatisfaction and discontentedness with normalcy; there must be more to life than stucco walls and loving one person forever.

Dating apps aren’t the only source contributing to this issue since Lasch’s ideas have evolved; social media in general has affected how we all think about dating, love and sex. The internet is limitless in terms of showing us the faces of new people, many of whom we will never even meet. Our dating pool is now pretty much anyone and everyone with a smartphone. Even if we aren’t consciously viewing every other social media user as a potential romantic interest, it is possible that we subconsciously store many of the people we come across in the back of our minds as options we may lose out on if we aren’t available. Therefore, the dissatisfaction people feel with their romantic connections affects even those who refrain from using dating apps.

Some may argue that keeping our options completely open is a good thing, but this is capitalist thinking and reminiscent of arguments that claim that having twenty different soft drink options is somehow a beacon of free choice and individual action. In reality, this causes us to be extremely disconnected from everything we purchase. The mass production of commodities only reinforces the capitalist ideal, which is simply overconsumption. Instead of bolstering freedom, free market capitalism coerces consumers into buying in excess. Nothing is special or meaningful since it is easy to buy and throw away and repeat the cycle. The same can be said about products and about people: both become disposable.

I am not saying we need to start marrying in our early twenties now, but the way that we look at love in these formative years is being warped. It’s okay to acknowledge that relationships at these ages may not last forever, but we are still developing our outlook on love and relationships in the midst of forming real behavior patterns that we will carry with us into the future. Dissatisfaction and disconnectivity in our personal relationships leads to an unhappy, unfulfilling life, as we become increasingly more concerned with ourselves and further isolated from our community, including loved ones.

Maybe it's inaccurate to view polycules and compulsive tinder swiping as the infection of consumerism spreading to our interpersonal matters. Regardless, the lack of real love in postmodern society is being felt by everyone. To defend ourselves from the vapidity of a consumer society, we should increase sensuality in our lives and connect to the world around us in meaningful ways. Sincerity is a form of counterculture in a society plagued by post-irony. Master your consumer impulses. Do things slowly and intentionally. Not just in your personal relationships, but in the mundanities of the day-to-day. Pray over your meals. Have a nighttime routine. Drink loose leaf tea. Believe in superstitions and don’t leave your shoes upturned on the ground. Treat the relationships in your life as if they are sacred, because they are.

To live is to suffer, there’s no way around that. Find someone who softens the blows.

PLAY: